- Sabbatical Anyone?

- My Sabbatical Plans

- Thoughts on My Last Day at Work

- Thoughts as I Leave

- Speaking with Authority! A Tale of an Ambassador and a Receptionist

- New Zealand: There’s no place like it

- There’s Life on the Third Planet!

- The Journey Is the Destination

- Down Under with the Aussies

- It Does a Father’s Heart Proud…

- Give Confidently, Give Generously

- A Taste of Thailand

- “We followed Jesus, and he led us to you”

- I’m in Rivendell!

- Charity and Discipleship

- Celebrations in India

- Karibu! Welcome to Kenya

- Rwanda: A miracle of renewal and reconciliation

- A Sermon on the Fly

- Effective Ministry in Malawi

- The promise of South Africa

- The Cost of Fear and Ignorance

- Saturday in London

- Easter in London

- Edinburgh: Castles, Churches, and Cellars

- Ancestral Roots in Paisley, Scotland

- Old buildings and modern people

- Curiouser and Curiouser

- My last ministry visits of the sabbatical

- Mon weekend à Paris

- Lest we forget…

- Among Friends in Zurich

- Backpacks, Spas, and Other Traveller’s Tips

- A Retreat to Close the Sabbatical

- The Strategy of Intentional Accidents

- My Wife, My COO, and a Director: Perspectives on My Sabbatical

- The Long-Term Benefits of a Sabbatical

Edinburgh’s Closes

If you lived in Edinburgh more than, say, 300 years ago, chances are good that you’d have lived a pretty miserable life. You, your spouse, and your eight to ten kids would be living in a one room house in a tenement situated on a close. A close (pronounced as in, “Close, but no cigar”) is a narrow alley off of a main street. In Old Town Edinburgh, the main street runs along the top of the hill and the closes run down the steep hill on either side.

Each close was a rabbit’s warren of tenements. At the high end of the street, the building might be two or three stories high, but at the low end of the street the building would be eight or more stories high—the world’s first high-rises.

You had one chamber pot that filled up quickly, and which twice a day had to be emptied. You would just open the door, shout “Gardez de l’eau!” and toss the contents out onto the street. Why French? I don’t know, but the phrase was contracted and mispronounced so that it became “Gardez loo!” and that is why the bathroom is called a loo in Britain—it means water.

The streets were not paved, and there were no sewers or gutters. Since you would have no shoes, you would hope that by the time you stepped onto the dirt street, or sent your kids out to play, that all the effluent would have drained down the hill! It was better to live at the high end of the street for sure. Poor people, merchants, tradesmen, and doctors would all live in the closes, their relative wealth merely determining which end of the street and how high up they could afford to live.

You would have no chimney, and the only opening in the house was likely your door and perhaps a window (but with no glass), so to cook and keep warm you’d have an open fire and just hope the smoke would dissipate on its own.

The closes are only four to six feet wide, and because the buildings were so high, the street was a very dark place. It was unlikely that you would see sunlight until you emerged onto the main street at the top or bottom of the close. The air you breathe would be rank and foul, and so, likely, you would be too. You might have one bath a year.

You would have lived a life of filth and disease, procreating enough children that perhaps a few may survive to adulthood, and then the cycle started again.

When touring places more than a couple of hundred years old, it’s easy to forget that most of what we see are the relics of the wealthy and privileged classes of history. They built in stone and slate, not mud and thatch. Their buildings were deemed worthy of preservation, not demolition. Their individual stories were documented, not forgotten.

We have insight into the life of a close because the Edinburgh city chambers were built on top of several closes. The upper stories of the buildings were leveled flat on the level of the main street. So only the basement at the top of the close is preserved, but lower down, several stories remain. These remains were made into the foundation on which the city office now sits. Mary King’s close is covered over, but otherwise still exists as it did hundreds of years ago, and you can descend into the cellars of the city and tour an authentic close today.

It’s easy to think our ancestors were just like us except for the lack of modern technology. But we need to consider the combined effects of the very different power structures of previous centuries, economic systems, religious thought, social conventions, and so forth. Lack of technology changes healthcare, life expectancy, education and travel, but those are just the tip of the iceberg.

Royal Residences

Edinburgh Castle

It’s a lot easier to learn about the lives of the rich and powerful. I learned a lot about the life of royalty from their residences. Edinburgh Castle, in common with all other castles, was not just a fort, but a residence too, and in this case, a royal residence. So it provided an interesting entree into Scottish history through the lives of its monarchs; politics, war, murder.

Hollyroodhouse

Hollyroodhouse, at the opposite end of the Royal Mile, is a more modern royal palace, still in use each summer by the Queen, so I learned not only about kings and queens from history, but about our present queen too.

Queen Elizabeth has never used the throne in the Throne Room. It hasn’t been used for generations. She sits in normal chairs or stands and meets people as you or I would. She never buys anything if she can help it. The day before I toured the palace she had sent some unused furniture from Buckingham Palace to fill up some space.

Royal Yacht Britannia

The other royal residence that I toured was Britannia. She has been taken out of service and is moored in Leith, Edinburgh’s port. Queen Elizabeth is nothing if not frugal. When she built the ship in the early 1950s, she reused all sorts of things from previous royal yachts. Machinery, decorations, furnishings, and finishings—a whole lot was recycled.

The engine room sparkles and is so clean it doesn’t look operational, yet it always looked this way, and when General Schwartzkopf was on board years ago and shown the engine room, he said, “Okay, I’ve seen the museum, now where’s the engine room?”

Queen Elizabeth did not want Britannia too ostentatious or ornate. She wanted it to feel like a country house, relaxed and home-like. The result is a yacht that is impressive for it’s size, not it’s decorating.

I saw ordinary wicker furniture such as you’d see at a cottage, and she used standard 1950s bedroom furniture that looked not much different from my parents’ bedroom suite.

Her bedroom was not even large. It couldn’t be, because when she was on board the crew of 60 or so was augmented by the palace staff of about 40. The state work still went on every day, so she needed her office staff. That’s a lot of people to put on any yacht.

There wasn’t much space for personal effects, but even so, each band member had 23 uniforms on board because the uniforms varied by which country they were visiting. Any crew who served above deck changed clothing an average of six times a day. They prided themselves on their spit and polish and impeccable dress.

Non-Royal Residences

I also learned a lot about the life of a lord, by visiting abbeys and chapels that they funded or owned. Those same places taught me about the life of a monk and the Cistercian and Cluniac orders as well.

John Knox was so important that buildings associated with him are still around, most notably the house he died in and St. Giles Cathedral.

Observations About Scotland

Here are a few observations from the first part of the week.

I picked up my rental car Monday morning to start this two week personal part of my sabbatical. After finally getting used to the turn signals being to the right of the steering wheel, this car has them on the left. You should try guessing how many times on three continents I have signaled my turns by first cleaning my windshield!

It was a very leisurely drive and quite an enjoyable scenic approach to Edinburgh on the A702. With a couple of stops, the trip took 8 hours.

The Moors

In my living room at home I have two watercolour landscapes of Scotland that my Mom gave me from her father’s house. One is of a moor that looks pretty desolate. The sky is foreboding, and off in the distance some sheep are grazing.

Both paintings are good examples of a genre called romantic landscapes. These were especially popular following the Industrial Revolution when people in cities looked back fondly on a more rural life in the past. It was part of the idealization that was typical of the Romantic era. Many of the artists had never seen the landscapes they were painting, and some landscapes were quite fanciful.

The moor in the painting is just so unusual that I thought it couldn’t exist, but on the A702 I saw moors very much like it. I was surprised and delighted. There really are such places! Even though I’ve never been to Scotland before and am generations removed from anyone who did live here, I couldn’t help feeling like I was returning home. I thought, “Ahh, the auld bonnie hills o’ Scotland!”

In real life, the moors are much more inviting than in the painting. They are green and have a different feel about them when in the sunlight. And there really are sheep here, lots of them, everywhere. Virtually any farm with livestock has sheep.

Speaking of animals, something else I’ve noticed is that there are no pretty dogs in Scotland. No lap dogs, no ‘foo-foos’ to carry around as ornaments! The Scots have handsome dogs, big dogs. I’ve seen lots of dogs and they are all dogs you can pat enthusiastically without knocking them over.

Roslynn Chapel

Roslynn Chapel was once famous for its elaborate stonework, but is now even more famous because Dan Brown invented a completely false history for the chapel in The Da Vinci Code. One of the pillars is amazing because it has a vine carved on top of it that climbs up encircling the pillar. It was carved by an apprentice who said God gave him the design. The master stonemason had been away for two years studying a new way to carve stone, and intended that this last pillar in the chapel would be his masterpiece, his legacy for posterity. When he came home and saw the pillar already finished, and then found out it was his apprentice who carved it, he was enraged both for the impertinence of the apprentice in carving it (forgetting the lord had given his permission) and for the fact that the apprentice, who should have no knowledge of how to do such work, could do such great work. The master stonemason picked up a mallet, and full of fury, killed the apprentice on the spot. The lord who was building the chapel thus lost both his stonemasons; one to murder and the other to execution.

Prior to the movie, about 9,000 people a year visited the chapel. That jumped to 170,000 the year after the movie came out! They had one toilet and two staff members. Since it is still an operating church, I asked the staff what it was like to suddenly have someone write something completely untrue about your building, and then be overwhelmed with tourists. Life cannot be the same. I said if I were the pastor I’d feel like the church had been highjacked. They said that was a good word to use, they have had their future highjacked, but it is not all a bad thing. The tour guides play up some of the mystery of the chapel, playing a bit to the crowd, but financially, they can now preserve the building in ways they could only dream of before. The day I was there, a crew was re-installing a stained glass window that had been out for a year being restored. Stone masons were at work chipping off a concrete layer that had been painted over all the stonework about 100 years ago. Rather than preserving the stone, the concrete trapped the moisture in it and hastened it’s decay. So thanks to Dan Brown, God has provided the funds to preserve this treasure. I thought it was hilarious when I saw the stone masons’ lean-to shed outside. No power tools in evidence. It looked just like the depictions I’ve seen of cathedrals being built, with all the various trades setting up their lean-to’s around the cathedral’s perimeter.

When the movie was being filmed, the crew discovered that the Star of David, a crucial part of the plot, is nowhere to be found in the chapel. It doesn’t exist, but the plot requires it to be found over the stairs to the crypt. So they made one on a circular piece of wood, and without permission attached it to the wall and painted it to make it look old. Unfortunately, when they removed it so the chapel wouldn’t know about it, the star left a clear white circle on the wall where none existed before. Lest in two hundred years someone devise another conspiracy theory to explain the circle, the official records of the chapel carefully document how this mysterious circle came to be.

Melrose Abbey

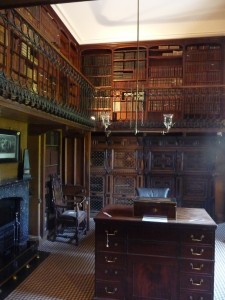

Melrose Abbey is one of the most evocative ruins in Europe that has inspired poets and artists alike. It is always hard to imagine what a ruin would have looked like when it was a whole building and in use. It is in a nice little village and is worth the trip. It isn’t very far at all from Abottsford, which is the manor house built by Sir Walter Scott. He must have been very wealthy to build such a grand place, surely one of the most financially successful writers in history. I don’t know much about him though. Perhaps he had other sources of wealth. I enjoyed the house and grounds. The first room I entered was a two-story library, complete with a small iron circular staircase to the walkway around the second level. I thought, “What a great library.” Then I walked through the other door into a room 10 times or more bigger, and that was the library! The other room was his personal study, where he wrote his books.

Dirleton

I visited Dirleton, reputed to be the prettiest village in Scotland. It was pretty, but I’m not sure if it was worth the drive or not. If you have time and want a country drive, go see it.

St. Giles

St. Giles’ Cathedral (where John Knox preached) was a surprise because the pulpit is in the middle, and the seats on four sides face it. It also has a fairly new, large pipe organ. Unfortunately I didn’t get to hear it. I was told the organist would be in about an hour later, but I didn’t have time to wait around.

John Knox House

The John Knox House (where he died), provides a good look into the lifestyle of wealthy people who could afford a house on the main street.

Scottish Parliament Building

I looked at the outside of the Scottish Parliament buildings and all I could think was, “Why?” They paid £414 million for a building that started with a maximum budget of £40 million and it looks like the fence around a village—sticks surrounding the building. I’m not sure which would win the ugliest building contest, the Scottish Parliament or the Mississauga City Hall. I did talk with someone from Edinburgh on the street, and he said he hates the outside, as most people do, but the inside is beautiful. Well, I didn’t have time to see for myself.

I thoroughly enjoyed Edinburgh and it’s surrounding area. Now I’m off to Paisley, the origin point for my mother’s family.